“Not for a split second have I thought of making a comeback.”

Words by Timothy John

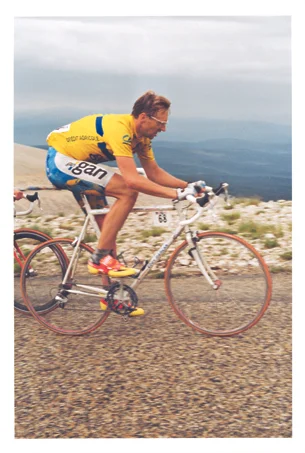

Photography courtesy of Rodale Books

It comes as little surprise that Jens Voigt has taken a definite view on his status as a former professional cyclist. His name was a byword for commitment. Now he is committed to a new life as an ex-bike racer.

Adjusting to retirement is difficult in any walk of life, but can be a dramatic change for a professional athlete, who grows accustomed to intense physical demands and the adrenaline rush and adulation that accompanies exceptional performance.

“I wake up some days and say, ‘Oh man, retirement is the best thing ever.’ Other days, it feels like someone has amputated a limb.”

Voigt says he studied former athletes and learned to read in small signs of bitterness the realisation that they had retired too soon, whether through injury or failure to land a contract. He is adamant that he has no regrets, no bitterness, no thoughts of a return to competitive action. Who of his generation left more of himself on the road? Not many.

“I left every competitive cell and thought out there. I squeezed every bit out of me, mentally and physically. Not for a split second have I thought of making a comeback.

“I raced Cipollini, Museeuw, Contador. I raced with Cancellara in his team. I had enough time to challenge myself against the best in the sport. I’m happy with the way my career went.”

Voigt describes himself as his biggest critic as well as his biggest fan, but he is only prepared to criticise himself, and speaks with real passion when he condemns retired athletes who make chippy comments about their successors.

He is optimistic, but not blithe. Too often, Voigt is portrayed as little more than a catchphrase, but he is an intelligent observer of professional cycling, and perhaps of life, too. This largely unknown side is revealed in a new book, inevitably titled, Shut Up, Legs!, which Voigt has co-written with Rouleur contributor, James Startt.

It contains the expected insights into team dynamics and personal friendships at GAN/Credit Agricole, CSC/Saxo Bank, and Leopard/RadioShack/Trek, as well as some characteristically frank views on doping, but the most interesting observations come when Voigt describes a childhood under Communism and his lifelong bemusement at the materialism of the West.

Death on the road

To return to the present: the death of Antoine Demoitié at Gent-Wevelgem was a long-heralded tragedy, but calls for more care in the convoy went unheeded. There can be little doubt that Voigt’s sympathies side with Demoitié and other riders to have been hit by race vehicles, but he cautions against a knee jerk response.

“What we shouldn’t do now is seek short-term, panic solutions. That doesn’t help. We need all the stakeholders to come together, step back and say, the cyclist is the number one priority. It’s called cycling: it’s not called car racing, or motor bike racing. Let’s make that clear one more time.”

He continues, however, to point out that the convoy has expanded massively since the 1980s, as has the circus that surrounds the biggest races, notably the Tour de France.

“Now there are helicopters, VIP cars, TV motorbikes. Somehow it’s all needed, because we can transport beautiful images directly to the world. But it’s a lot of traffic on the roads.

“I don’t know where we cut it. VIP cars don’t help the race, but if a race organiser puts in €1m or €2m, how we can deny that person or that sponsor the experience? We all like to see crystal clear images of ourselves in Rouleur Magazine, but should we cut down on photographers?”

Voigt believes vehicles in the convoy should be offered a deviation from the race route every 20 or 30 miles and with it a chance to pass the peloton safely.

Family guy

James Brown claimed a voracious work ethic, but not even the self-styled “hardest working man in show business” could claim to match Voigt in watts expended. Shirking was as alien to the mullet-rocking East German as it was to Soul Brother Number One.

Voigt gained his work ethic at an early age, growing up in what he describes as a working class family, where his father worked as a blacksmith and his mother as a photographer who spent hours at a time shut in a dark room, processing negatives.

“For the first 14 and-a-half years of my life, we didn’t have a car,” Voigt recalls. “We went everywhere by public transport; by bus or train. We didn’t have a phone until I was 16 or 17. In East Germany, the government would only give you a phone number if they’d tapped it first.”

The hyperactive kid, small for his age, tested well in applications to a national sports school and at 14 embarked on a path that would lead, ultimately, to the WorldTour.

“I won a few races, and lost a lot more,” he reflects, and it says much for Voigt and his legions of admirers that no one much cares about his win ratio. Courage and commitment to the cause counted with him more than victory.

Voigt’s good humour shouldn’t mask the fact that he was a warrior, however. With a more menacing demeanour, he might have been pigeonholed among rouleurs more readily granted the reverence of the cognoscenti. Voigt was race smart and a useful climber, as well as an indefatigable workhorse.

“My job was not to be normal,” he tells me. “It was not to be mortal. People like me because I did extraordinary things: 140km in the breakaway in the USA Pro Challenge to win by six minutes? People say, ‘Wow! That’s important’.”

He does not consider himself in danger of falling into the black hole of depression that engulfs many world class athletes when they retire. He points to his wife and six children as the safety net.

“Your children love you regardless,” he says. “Your kids love you because you’re dad, because you’re there for them. That’s my security network.”

Voigt no longer needs to prove himself “immortal”. His capacity for suffering will doubtless pass into cycling lore, along with his catchphrase, but there is much more to Voigt, an intelligent man whose optimism and innate belief in the simple life should not be confused with naivety.

“Life gets really complicated really quickly by itself,” he tells me, paraphrasing his father’s wisdom. “We should start with a simple plan."

Shut Up, Legs! My Wild Ride On and Off The Bike is published by Rodale Books on May 3, 2016